Sunny climate, stormy climate | Weekly digest #17

This week we talk about Burning man, the extinct bird that's returned to New Zealand, the driest August India has seen since 1901, and a historic referendum in Ecuador

For the ones who are new here - Every week I bring to you 5 stories about the changing climate and its impact on us!

3 stormy ones - concerning stories that are a source of alarm

2 sunny ones - green shoots that tell you that all is not yet lost

If you would like to get future editions of the newsletter delivered to your mailbox, please hit subscribe.

Sunny news

Takahē, a prehistoric bird that was once thought extinct returned to the wild in New Zealand

The takahē is a large, flightless bird, that was believed for decades to be extinct.

Last week, 18 of the birds were released to the wild in the Lake Whakatipu Waimāori valley, an alpine area of New Zealand’s South Island.

Like a number of New Zealand birds, the takahē evolved without native land mammals surrounding them. Their presence in the region dates back to at least the prehistoric Pleistocene era, according to fossil remains.

The birds had been formally declared extinct in 1898, their population devastated by the arrival of European settlers’ animal companions: stoats, cats, ferrets and rats.

Efforts to bring them back have been ongoing for more than 70 years after they were rediscovered in 1948. Conservationists first started by incubating eggs in labs and then breeding in captivity to protect them from pests. At present, there is a population of ~500 in labs, island sanctuaries and national parks. This is the first time the birds have been reintroduced to the wild and if this works, will be a huge win for conservationists.

This work to sustain takahē is part of a wider effort in New Zealand to protect its unique, threatened birds.

Sources to read further:

Ecuador shows through its vote: It’s possible to say no to oil.

In a historic referendum, the people of Ecuador voted last Sunday to permanently stop drilling for oil in Yasuni, a protected area in the Amazon.

The referendum result obliges the state oil company to dismantle operations – 12 drilling platforms and 225 wells that produce up to 57,000 barrels a day – in block 43 in an area called Yasuni.

This area is one of the most important biodiversity hotspots in the world and is home to two indigenous non contacted tribes. It is home to at least 1,300 native tree species and more than 100,000 different types of insects per hectare.

How did we get here?

The oil reserve in the national park that was valued at USD 7.2 bn was discovered in early 2000s and prompted a fierce debate

In 2007, Ecuador’s then president, Rafael Correa, proposed to the United Nations General Assembly that the fossil fuels could be left in the ground if the international community would provide half that amount to that state. Donations came in but not nearly close to the necessary amount.

Soon oil firms started building roads to the drilling site. The roads opened the ways for loggers and poachers, oil spills contaminated the earth and water, and the increased noise and light disturbed wildlife.

It is estimated that more than 600 hectares have been deforested in Yasuní, mostly by the oil industry.

This referendum is the fruit of years of dogged campaigning by the Yasunídos collective and other civil society groups. The government initially refused to accept a petition with 750,000 signatures, even though this was nearly double the threshold needed to initiate a referendum. Years later, the courts finally ruled that the proposal should be put to vote.

Why does this matter?

With more than 5.4 million votes in favour of halting production and 3.7 million against, this is the most decisive democratic victory against the fossil fuel industry in Latin America and, arguably, the world.

It is a potential model for how we can use the democratic process around the world to help slow or even stop the expansion of fossil fuels.

The referendum has given other governments a glaring example of the cost of stranded assets when the social mandate for fossil fuels is suddenly removed. It will make other governments think twice before investing in new oil projects.

The most important message from Ecuador’s referendum though is the simplest: It is possible to say no to oil.

Sources to read further:

Stormy news

Burning man turns into a mudfest. Thousands stranded after heavy rain, told to conserve food and water.

The site of Burning Man turns into mud after the area gets 2-3 months of rainfall in 24 hours; Source: NBC News What is Burning Man?

It is an annual festival that has taken place since 1986 focused on "community, art, self-expression, and self-reliance"

A temporary city is erected at Black Rock City in northwestern Nevada, where the 9 day festival takes place. Almost 80k people including artists and tech titans attended the event in 2019.

The name of the event comes from its culminating ceremony: the symbolic burning of a large wooden effigy, referred to as the Man

What happened this year?

This year the festival was scheduled to take place from Aug 27 to Sept 4.

On Friday Sept 1 a thunderstorm turned the site of the event in Nevada desert into mud. Overnight, Black Rock City had received around 0.6 to 0.8 an inch of rain.

As a result of the rain, the roads to and from the site of the event were completely shut. The region was under threat of flash floods over the weekend and the roads were expected to remain shut for the next couple of days.

Attendees at the festival site were asked to ‘shelter in place and conserve food and water’. Internet is limited and it is impossible to walk through the mud.

Attendees on their way to Burning Man were advised to "turn around and head home."

One person is reported to have died, but we don’t yet know how.

Well, is this linked to climate change?

This kind of rainfall is extremely unusual for the region. Rainfall reports from the National Weather Service suggest up to 0.8 inches of rain fell in the area from Friday morning through Saturday morning – approximately two to three months of rainfall for that location this time of year.

Even an inch of rain is rare for this Nevada region, making the ground unable to absorb the water without creating runoff and mudflows.

Sources to read further:

India: This was the driest and warmest August since 1901

India has experienced its driest and warmest August since records began in 1901.

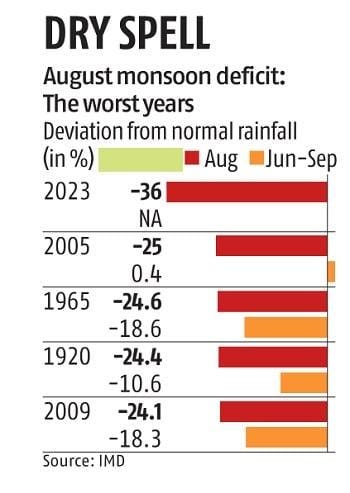

Monsoon precipitation in August has been the lowest in 122 years since 1901, the IMD said on Thursday.

We got 167 mm of rainfall in August, against an average of 254 mm expected for this month (a 36% deficit) . The previous lowest was 190 mm seen in 2005.

The avg. maximum temp for August was also the highest ever since 1901.

IMD's Director General, Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, attributed the August rainfall shortfall primarily to El Nino conditions, characterized by elevated temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which tend to suppress rainfall.

What will this impact?

Impact of uneven and erratic monsoons is already visible in kharif sowing. Although overall Kharif sowing is almost over and 3.6% higher year-on-year at 105.4 million hectares, area under pulses lags significantly and cotton and oilseeds to some extent.

If rain in September continues to be lower than average, it will affect the flowering of crops and consequently the produce.

Reservoirs: The gap in water levels at 150 key reservoirs across the country is lower by at least 23% as against the corresponding period last year.

Source to read further:

Climate crisis could mean that 25% of Europe’s ski resorts face scare snow putting them at risk.

Snowmaker sprays snow on the piste for mountain skiers. Credit: Sergey Podkolzin / Alamy Stock Photo Currently, we are on track to get to 2.7 deg of warming above pre-industrial levels.

A recent study found that 53% and 98% of Europe’s ski resorts are projected to be at very high risk for snow supply under global warming of 2C and 4C, respectively.

It is already common to use snow makers to make artificial snow to make up the deficit.

With artificial snowmaking the proportion of affected resorts is reduced to 27% and 71% of ski resorts, respectively. So even with artificial snow making at least a quarter if ski resorts will not have sufficient snow to continue operating.

Particularly, snow making is unlikely to help in resorts in Britain and southern Europe, where it will frequently become too warm to create snow in the first place, or the snow that can be made will melt very quickly.

Also, additional snow making will have its own adverse impact – by increasing water and electricity demand, it will add to the considerable carbon footprint of the ski industry, which is typically mostly due to transportation and housing.

Sources for further reading: